How to prompt LLMs with private data?

by Haonan Duan, Adam Dziedzic, Nicolas Papernot, and Franziska Boenisch

Over the past few years, large language models (LLMs) have gained widespread attention in both the tech industry and academia, as well as the public at large. LLMs are capable of executing a wide range of language-related tasks, such as translation, text generation, and sentiment analysis. One particularly amazing property of LLMs is that they need only minor modifications to handle new tasks, making them particularly well-suited for the rapid development of new applications.

In many scenarios, a company might want to adapt these pretrained LLMs with data that contains sensitive information. For example, Epic, a healthcare software company in the U.S., is recently partnering with Microsoft to integrate GPT4 in managing patients’ electronic healthcare records. Adapting LLMs to this data naively could expose patients’ sensitive information. To prevent these privacy violations, we have to be careful how we construct the prompts we query the LLM with - as we will explain next.

What is ‘prompting’ for LLMs?

Generally speaking, there are two standard ways to adapt LLMs to new tasks, “fine-tuning” and “prompting.” The first way, fine-tuning, updates the parameters of the LLM to better reflect the new task. The second, prompting, does not make any updates to the original LLMs. Instead, it adds examples to provide context for the input that the user submits. This is done directly when the model is asked to predict on an input from the new task.

A canonical type of a prompt contains a brief instruction of the task, followed by several examples of the task in the form of an input and output pair. For example, an LLM could be used to recognize whether the sentiment of a movie review was positive or negative using a prompt that looks like this:

Instruction: Given some text, classify whether it is positive or negative.

Input: the movie was great.

Output: positive

To get the model’s prediction on a new movie review, we would prepend the above prompt to the new query “Input: the film was rather boring.” The model would then output the following: “Output: negative”.

Why prompting?

Prompting offers several advantages over fine-tuning. First, prompting is very storage-efficient. Storing a separate fine-tuned model for each new task can be expensive because LLMs have lots of parameters. Instead, prompt tuning only requires storing a small prompt to provide task-specific context.

Second, the computation costs of fine-tuning become increasingly prohibitive as the models’ sizes grow. Prompting, as stated, works without tuning all of the model parameters.

Third, many LLMs are deployed behind APIs–a restricted interface for two or more computer programs to communicate with each other. This means that the end user does not have access to the model parameters. The only way to adapt the model in this case is through prompts.

The privacy risks of prompting

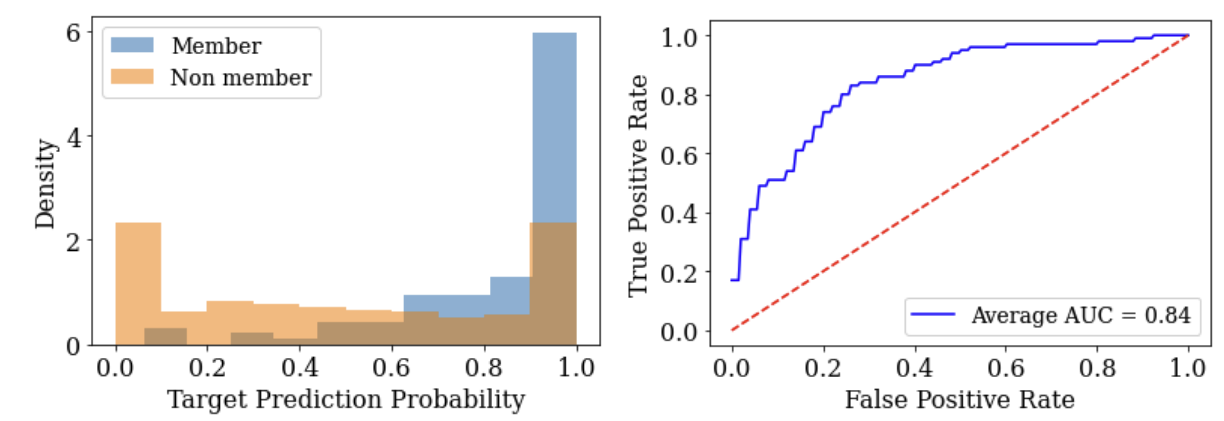

When we started our work, little was known about the privacy implications of prompting. The first question we asked ourselves is: do LLM predictions leak sensitive information contained in their prompts? To measure this, we carried out what is called a “membership inference attack” on model predictions. Given a particular example, this attack tries to figure out if the LLM used that example in its prompt when making predictions. This may be a very simple attack - but it can be used to construct much more sophisticated attacks like attacks that reconstruct the examples contained in prompts. Here are the results from this first experiment.

The left figure shows that the LLM is much more confident when being asked to predict on an input which it already appears in the prompt (as indicated in blue) than when it is asked to predict on an input that was not in the prompt (as indicated in orange). This means the adversary can “guess” that an example was in the prompt by looking at the examples for which the model is confident were in the prompt. The right figure shows that this guess is often a correct one. The ROC curve (receiver operating characteristic curve) of this attack demonstrates the adversary (indicated with the blue curve) is more likely to succeed than if it had guessed randomly (using a coin flip, as indicated by the red dotted line). Indeed, the further away the blue line is from the red line, the more successful the attack is.

Put altogether, this first experiment shows that there is significant risk when one includes sensitive data in the prompts that are given to LLMs. So, we set out to find a solution.

Privacy-preserving prompts

To protect privacy, intuitively, we would like to ensure that none of the examples contained in the prompt “influences” the outputs of the prompt too much. This way, when the LLM makes predictions from the prompt, its output won’t reveal too much information about the particular examples that were used to construct the prompt. It turns out that the research community has developed a framework to capture this intuition more rigorously - this framework is called differential privacy (DP). If you are interested in more details on differential privacy, you are welcome to check out our earlier blog post on the topic.

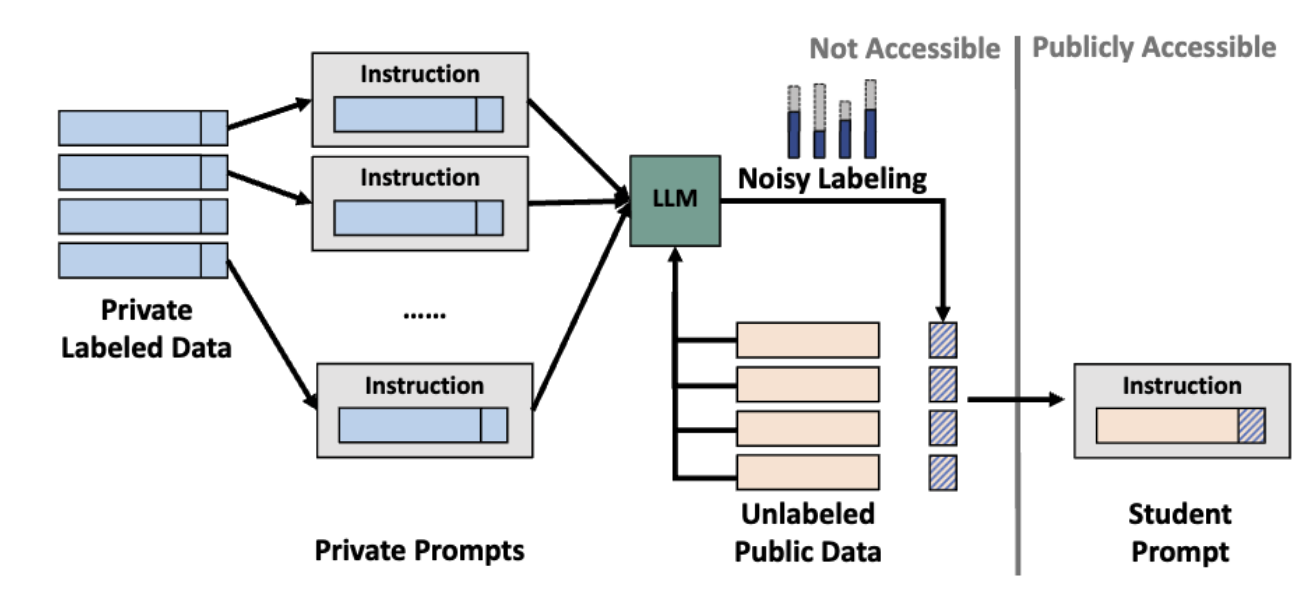

How can we construct prompts with differential privacy? First, we prompt the LLM with different prompts, each of which contains a disjoint subset of examples from the private dataset. Given an (unlabeled) input, each prompted LLM outputs a prediction based on its own prompt. Then we gather all the predictions from each prompted model and output the prediction that most models agree with. Intuitively, this “voting” process makes a prediction based on the information contained in multiple data points and reduces the influence that each data point has on the overall prediction made.

The above process alone is almost but not quite sufficient to provide differential privacy guarantees. To rigorously protect the privacy of the examples contained in the private set, we have to add noise to the models’ votes before we output the consensus. This approach is indeed well-established in the privacy-preserving machine learning literature. It is called Private Aggregation of Teacher Ensembles (PATE). For a detailed introduction to PATE, we refer you to our another blog post.

We then select the best pair of input and aggregated label and use that pair as the example that makes up our prompt for the LLM model. We refer to this prompt as the student prompt because this prompt was obtained by distilling the knowledge the teachers had acquired.

The diagram below illustrates this approach.

We implement this PATE algorithm with two popular commercial LLM APIs, GPT3 and Claude. Our results show that the method offers very strong privacy protection for data contained in prompts as well as high prediction accuracy when using our private prompts. Our method is the first privacy-preserving algorithm that can be employed with all commercial APIs.

A subset of commercial APIs may provide additional access to the user. For instance, they may allow the user to compute gradients with respect to the inputs of the LLM being queried. When we have such access to the model, we can deploy another approach to obtain prompts that protect privacy.

These prompts are different to the ones we described until now. So far, we used what is called discrete prompts: the prompts were made up of real words. Yet, LLMs internally represent words as vectors of numbers. This can be exploited to prompt them more precisely. We call this type of prompts soft prompts, the LLM is prompted with vectors of numbers directly (rather than real words that are then later converted into vectors of numbers).

Since soft prompts are made of numbers, we can construct them using a search procedure that is based on gradient descent. Luckily, gradient descent is the most common way to train neural networks. Hence, the privacy community has devised numerous algorithms to make gradient descent differentially private. In particular, one algorithm stands out: differentially private stochastic gradient descent. It clips and noises gradients to make them private. Why do these extra steps protect the privacy of training data? Intuitively speaking, clipping the gradients ensures that an example cannot influence the model update too much, and adding noise obfuscates the particular updates that were applied to the model. Thus, by modifying the gradient descent procedure in training the soft prompts, the data used to train the soft prompts has a differential privacy guarantee.

Conclusions

Our work identifies the privacy risk of prompting and offers methods to construct discrete and soft prompts that preserve privacy. We find that prompting is a practical and efficient way to adapt LLMs with differential privacy. There are still many improvements that can be made to our algorithm. For example, it is interesting to see how to extend our approach to protect users against malicious LLM providers. We hope that our work will inspire others to work on this problem.

If you’d like to learn more, read our NeurIPS 2023 paper “Flocks of Stochastic Parrots: Differentially Private Prompt Learning for Large Language Models”. It goes into greater detail about our research on this topic.