On stealing and defending self-supervised models

by Adam Dziedzic and Nicolas Papernot

This blog post is part of a series on model stealing, check out our previous blog posts “Is this model mine?” for a general introduction to the problem and a new active defense against the extraction of supervised models “How to Keep a Model Stealing Adversary Busy?” .[1]

Machine Learning (ML) models cater to tasks such as language translation, speech recognition, data annotation, or optical character recognition. The models that fulfill these tasks are publicly exposed via APIs. They are trained in either the supervised or self-supervised setting. The supervised models are expensive in terms of data labeling but their training cost is relatively inexpensive. On the other hand, the self-supervised models have zero cost of data labeling. They can leverage all the available data points but such an approach increases the training cost of these models. The creators of the models want to prevent them from being stolen. In this blog post, we analyze how to steal and defend self-supervised models [2] , [3]. The threat of stealing self-supervised learning models is real. An attacker’s incentive is to steal a model at a much lower cost than training it from scratch. Recently, researchers showed that training a ResNet50 SSL model costs north of $5713.92, whereas stealing such an encoder costs only around $72.49 [4].

Self-Supervised Learning

Self-supervised learning (SSL) emerges as a dominant learning paradigm behind modern ML APIs. The major paradigm shift is that these large self-supervised models, called encoders, are trained on a big amount of unlabeled data. These SSL models return high-dimensional representations instead of low-dimensional outputs such as labels. The representations are features extracted from a given input query and they can be used for many downstream tasks. For example, you can send a block of text as input and receive an embedding as output, which is offered by an API exposed by Cohere [5]. Going from supervised to self-supervised learning is essential and it is the future of the ML APIs. It is essential since representations can be re-used on many tasks and you need a small number of labels to train downstream tasks. A company that offers such an API does not have to know all of the labels required by a given client but they provide a generic interface that extracts useful features for a given input. First, we will show how to extract encoders and then present methods to detect if a given encoder is a stolen copy of a victim encoder.

How to Steal Self-Supervised Encoders?

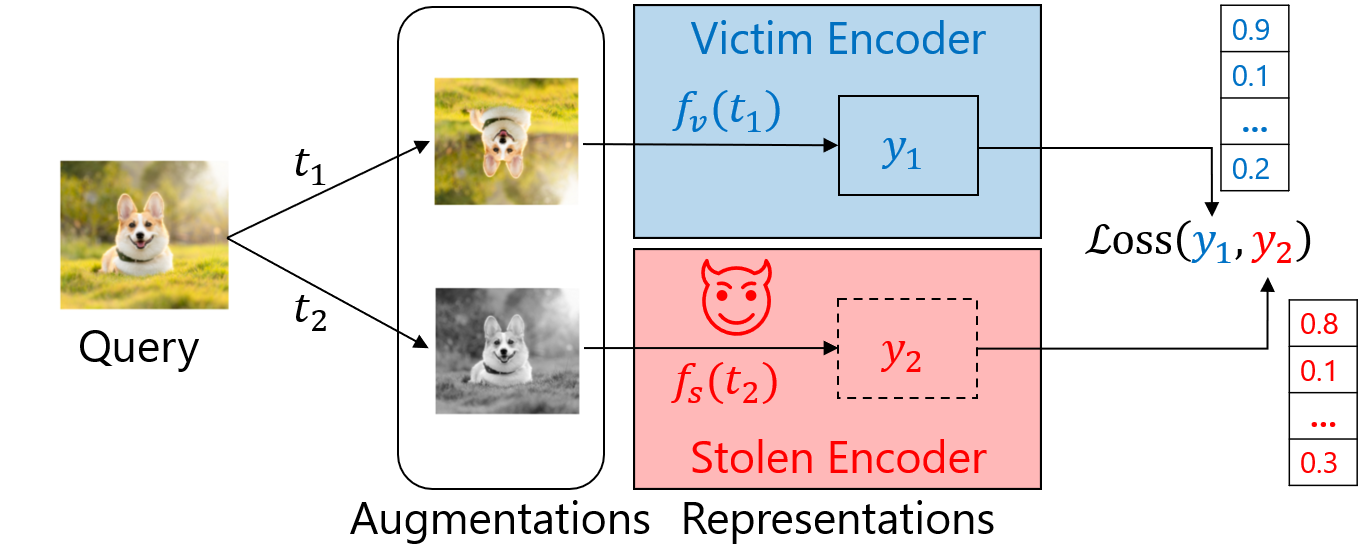

The framework of our attacks is inspired by Siamese networks. For an input query, represented as an image of a (corgi) dog (in the diagram below), we generate two augmentations by applying vertical flip and grayscale transformation. Then, we query the victim encoder with the first augmentation and our stolen copy with the second augmentation. To steal the victim encoder, we train the stolen encoder to minimize the loss between representations obtained from the victim encoder \(y_1\) shown in blue, and representations from our stolen copy \(𝑦_2\) shown in red.

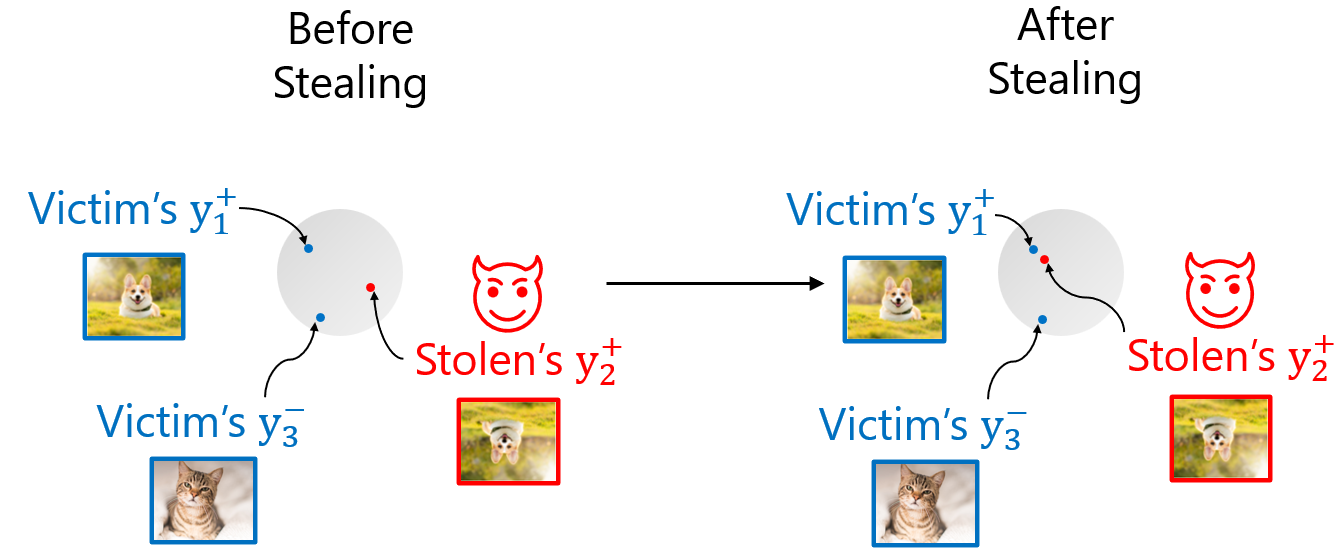

To this end, we apply contrastive loss functions (see the image below). In the representation space, before stealing, the positive pairs (two augmentations of the same image \(y_1^+\) and \(y_2^+\)) from the victim and stolen encoders are far from each other. After stealing, the positive pairs are close to each other. Thus, the stolen encoder replicates the behavior of the victim encoder. The crucial point of contrastive loss functions is that the positive pairs stay close to each other but also the negative examples (\(y_1^+\) and \(y_3^-\)) coming from different inputs are far from the positive pairs. The selection of the loss function is one of the most important hyper-parameter for stealing encoders. We compared standard losses as well as modern batch contrastive losses. The standard loss like Mean Squared Error is used to directly minimize distances between representations from the victim and the stolen copy. Modern batch contrastive losses like InfoNCE [8] or Soft Nearest Neighbors [9] compare not only positive but also negative pair samples. We find that contrastive losses perform the best for both training and stealing encoders and allow us to decrease the number of stealing queries to be less than 1/5th of the number of victim’s training data points.

How to Defend or Detect Encoder Stealing?

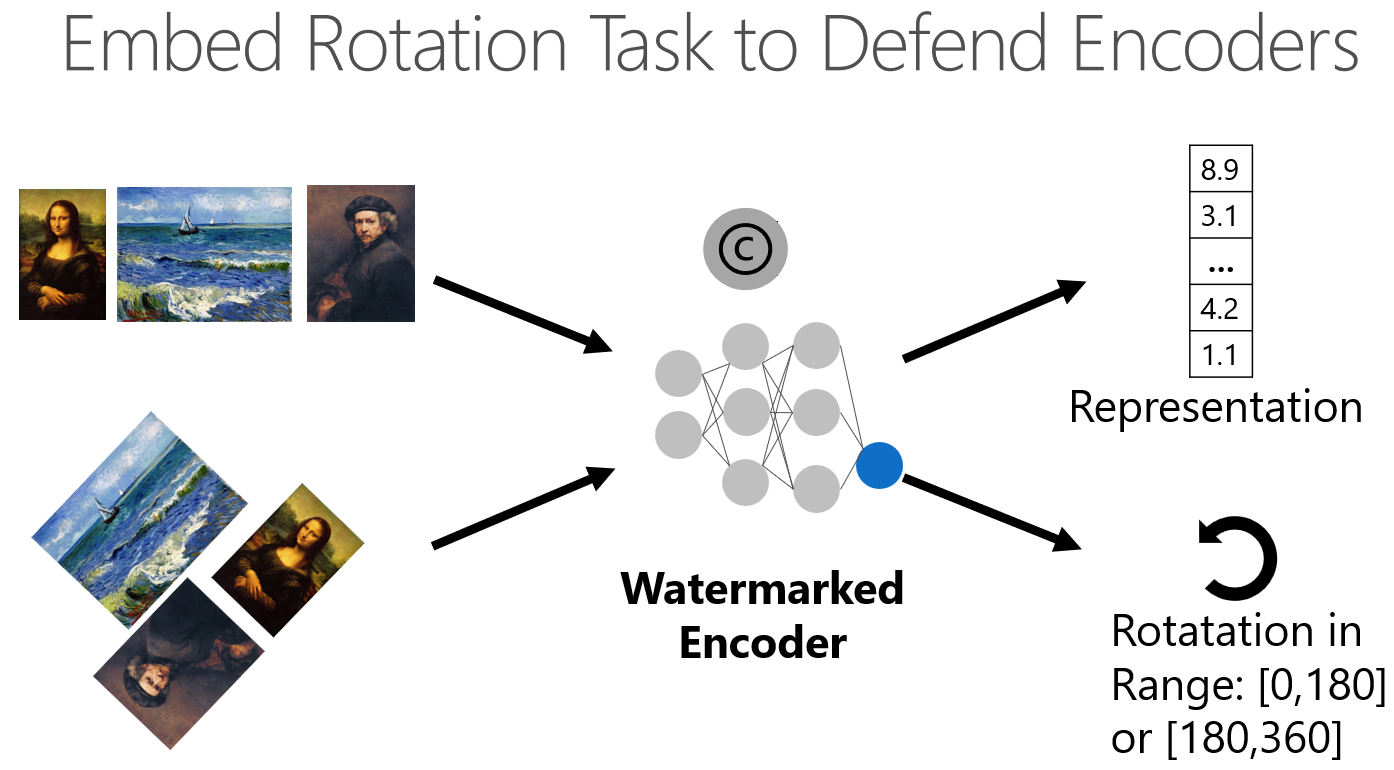

Having discussed how to steal encoders, let us consider defense methods. The active defenses either perturb or truncate the answers to poison the training objective of an attacker but they were shown to harm substantially the performance of legitimate users so they are not usable in the SSL setting [6]. The watermarking based defenses, for example, embed a unique task into the encoder, which marks the encoder as our property. If we can prove that the stolen encoder also has our unique property, then we can detect a theft. During standard training of encoders, we provide as inputs images and train the encoder to generate high-quality representations. For watermarking, we embed the rotation task into encoders during training. As an example, the task is a binary classification where we have to classify if a given image is rotated between 0 and 180 degrees or between 180 and 360 degrees. To implement the watermark, we add the additional fully-connected layer on top of the representations. Whenever we tune the parameters for the rotation task, we also adapt all the other weights in the encoder. As a result, the watermarked encoder and its stolen copies return not only embeddings but also the correct rotation range (see the schema below). We observe that for a legitimately trained model, the watermark task achieves near-random accuracy of 50%. On the other hand, for a stolen encoder, the more queries are used for extraction, the higher transfer of the watermark (> 50%). This holds across many loss functions used for stealing.

However, first, watermarking requires retraining or fine-tuning the large encoders, which is impractical. An adaptive attacker can use different extraction methods to lower the transfer of the watermark from the victim to stolen encoders. There exist many methods to remove watermarks. For example, in the case of the rotation watermark, an adversary can obfuscate the representations to fool the detection of a watermark. To tackle the problems of watermarking, we propose a new method to detect a stolen encoder. Our approach is based on dataset inference that treats the training data of a victim encoder as its signature [7]. This detection method is effective and does not require encoder fine-tuning.

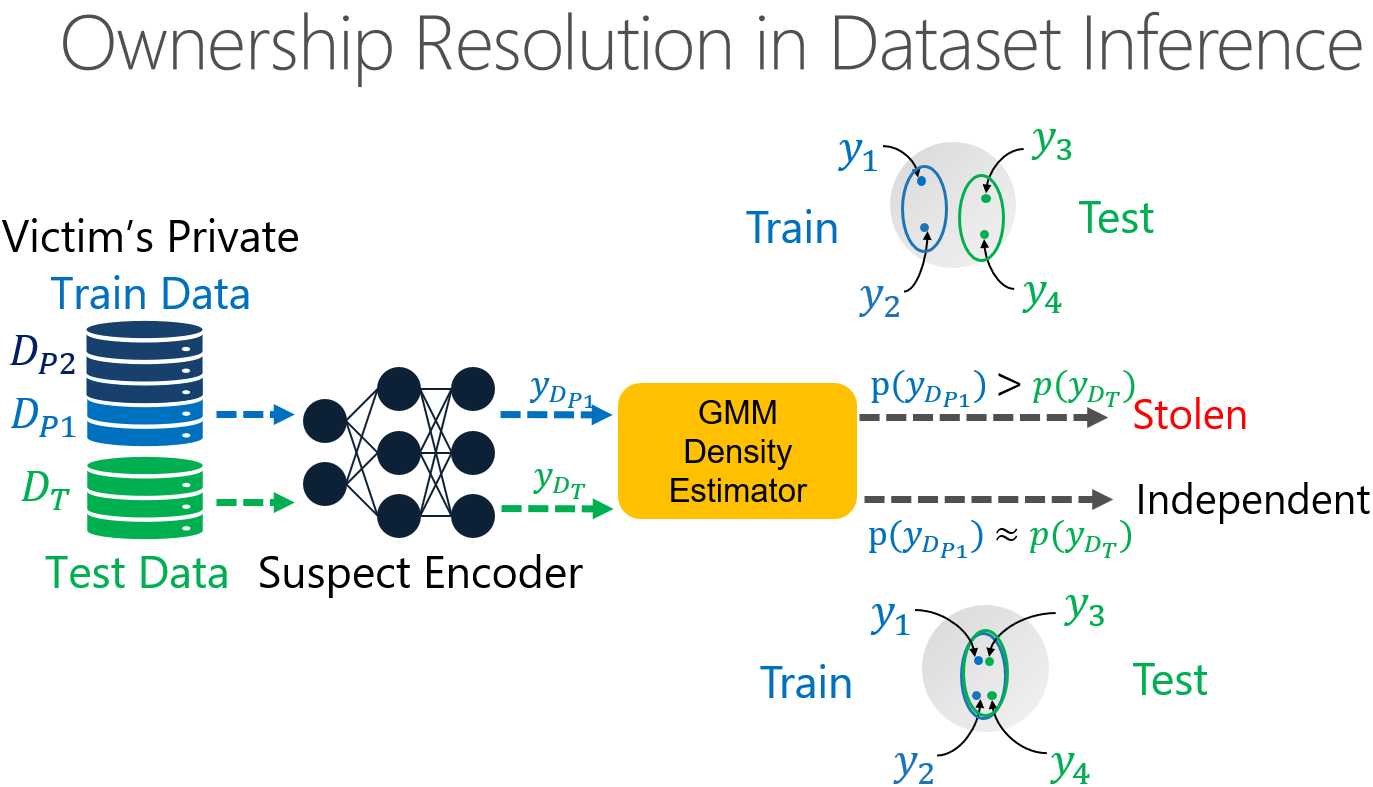

For the resolution of the ownership, we assume that we as a defender have access to our training and test sets as well as the query access to a suspect encoder. Training and test data come from the same distribution. The first step in our method is to train a meta model, in this case a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) to estimate the distribution of representations. We use part of the traing set to do so. To resolve the ownership, we compare the log-likelihoods for the train vs test sets. In the case when the log-likelihood is much larger for the train set, we mark the tested encoder as stolen. Otherwise, if there is almost no difference in the log-likelihood between the train and test sets, then such an encoder is marked as an independent encoder. How do we quantify if the difference between the log-likelihoods of representations are significant? We do it by harnessing statistical testing. Concretely, to verify the ownership we use a statistical t-test. The null hypothesis is that there is no difference between the log-likelihood for train and test sets. If the p-value is below a certain threshold (e.g., 1%,) then the encoder is either the victim or stolen. Otherwise, the t-test is inconclusive and the suspect encoder is marked as independent, meaning not stolen.

Summary

Let us summarize the main aspects stealing attacks and defenses for SSL models. Recent attacks on the SSL models show that high-quality encoders can be extracted at the fraction of the cost of creating the victim encoders. We described how we can detect stolen self-supervised models by using the victim’s training and test data as the model’s signature. The crucial intuition is that an encoder that was trained on the given training data or stolen from such victim behaves differently on the training data vs the test data. On the other hand, an independently trained encoder behaves similarly on both the train and test data. As of now, we can only detect stolen encoders. Defending encoders against stealing attacks is challenging since representations leak large amounts of information and the existing defenses cannot be applied out-of-the-box to protect encoders. Thus, there is a need to create active defenses for self-supervised models which would not harm legitimate users but could increase the cost of encoder extraction.

Want to read more?

You can find additional details in our ICML paper [2] and the NeurIPS paper [3]. The code for reproducing all our experiments is available in our GitHub repositories: SSLAttackDefenses and DataSetInferenceForSelfSupervisedModels .

[1] Adam Dziedzic, Muhammad Ahmad Kaleem, Yu Shen Lu, Nicolas Papernot. Increasing the Cost of Model Extraction with Calibrated Proof of Work ICLR 2022.

[2] Adam Dziedzic, Nikita Dhawan, Muhammad Ahmad Kaleem, Jonas Guan, Nicolas Papernot. On the Difficulty of Defending Self-Supervised Learning against Model Extraction ICML 2022.

[3] Adam Dziedzic, Haonan Duan, Muhammad Ahmad Kaleem, Nikita Dhawan, Jonas Guan, Yannis Cattan, Franziska Boenisch, Nicolas Papernot. Dataset Inference for Self-Supervised Models NeurIPS 2022.

[4] Tianshuo Cong, Xinlei He, Yang Zhang. SSLGuard: A Watermarking Scheme for Self-supervised Learning Pre-trained Encoders CCS 2022.

[5] Luis Serrano. What Are Word and Sentence Embeddings?

[6] Yupei Liu, Jinyuan Jia, Hongbin Liu, Neil Zhenqiang Gong. StolenEncoder: Stealing Pre-trained Encoders in Self-supervised Learning CCS 2022.

[7] Pratyush Maini, Mohammad Yaghini, Nicolas Papernot. Dataset Inference: Ownership Resolution in Machine Learning ICLR 2021.

[8] Ting Chen, Simon Kornblith, Mohammad Norouzi, Geoffrey Hinton. A Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations ICML 2020.

[9] Nicholas Frosst, Nicolas Papernot, Geoffrey Hinton. Analyzing and Improving Representations with the Soft Nearest Neighbor Loss ICML 2020.